In the Aftermath of the Silicon Valley Bank Failure

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), a huge Californian tech-lending bank and VC with a balance sheet of $290 billion, collapsed out of blue. This failure has now been recorded as the second largest bank collapse in the US financial history after the Washington Mutual in 2008, which had then swooshed a larger balance sheet of $ 370 billion into nothing.

The case is critical at the micro level since many people will have lost maybe their lifetime savings at the end of this case since FDIC only insures deposits up to $250K.

From a macro point of view, the case presents too many complexities again for it now probably – indeed, most likely – limited the Fed’s maneuvering space. As we all know the US economy is still fighting against inflation and Fed has stated openly and recently that the interest rates are not to be relaxed by the Fed anytime soon. The conundrum the Fed had to resolve until now was to follow a monetary policy so tight that inflation would be subdued but not tighter than required for the sake of not pushing the economic growth down the hill. But now, after SVB, everybody will focus on the health of the US banking sector. And the broader picture they will see is the following.

It is a working capital problem. US banks may need liquidity support.

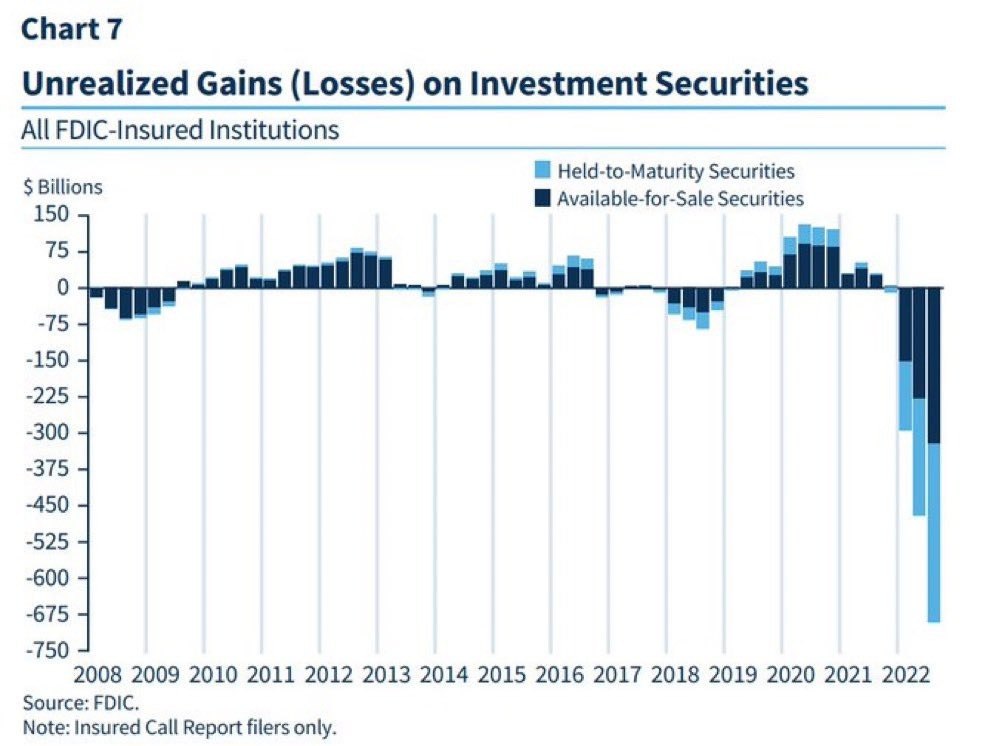

As it is seen, 2022 has been a pivotal year when the investments of FDIC-insured institutions turned negative at unprecedented amounts. The interest rate hikes of the Fed have surely depressed the market value of government bonds and other fixed-income instruments and that seems to have washed off a sizable amount of wealth from the US banks’ balance sheets. (Figure 1)

The decline in the secondary market values of bonds is a problem for US banks because it makes liquidity management harder for them. At the end of the day, like in any other company, if the market value of the marketable securities declines radically, that causes a meltdown in the working capital. And the health of the banks’ working capital rests on the quality of two stock values of two assets on their balance sheets: i) loans and ii) securities.

As I have underlined in the opening paragraph, SVB was a tech lender. And the technology sector has not done well in 2022 as we all know. That is a clear fact when we look at the prices of tech giants’ shares or their massive layoffs. A profitable sector with a shiny future outlook would not be so obsessed with cutting costs as the US tech giants now do. SVB had exposure to this sector — massively. As if that was not cursing enough, the interest rate hikes – as aforesaid – washed off a good amount of the value of the marketable securities held by the US banks. In our reckoning, SVB’s story is not unique to a single bank, and by no means are the risks of contagion contained. The declining value of the bonds investments and significant exposure to the tech sector must be the problems of many banks across the whole US.

Then, could that incidence trigger a financial risk for the whole system?

That is of course a possibility but regulators and the Fed will surely try to tackle such a serious risk and come up with some measures. But that leaves us with the question of what the Fed can do. The Fed will surely feel the need to support the working capital of the US banks. But since it would not overturn its interest rate policy (The Fed already said that it will not relax the US interest rates anytime soon until the inflation goes away for sure, so declining interest rates and restoration in the secondhand value of bond stocks is not an option), it has to do something else for bettering of the liquidity access of the US banks.

One thing that FED may try in this regard could be an expansion of the repo and swap facilities with the banks. And prolonging the time horizon of the repo and swaps with the banks should also be considered. But the aim of this article is not to discuss what kind of tools precisely the Fed can or will use. In our reckoning, they will surely take this incident so seriously and the step that they will take will surely be a step in the direction of increasing liquidity access to the US banks. Such a move would require fine adjustment as the Fed would also be fighting a battle against inflation. But sending the strong signals of the Fed’s and other regulators’ preparedness and determination to stand ready to bail out the US banking system if need be is critically important since a US banking sector crisis would drown Europe as well.

Is Credit Suisse Safe?

Last year, there were rumors about when, rather than if, the Swiss banking giant Credit Suisse would fail. A US banking sector collapse could trigger a collapse in Europe, too, and it needs just one banking giant’s collapse to trigger a bank run. The recent history might be illuminating for us to understand the perceptional connectedness of the markets. That is to say, we always tend to look at the amount of capital invested in one country by the residents of another to see whether contagion effects are likely to kick in if one of the countries fails but the reality is much more complex and has a psychological depth, too. Indeed, markets already seem to be front-running the adversity of the issues that broke out in the US for the European banks. (Figure 2)

In order to understand the connectedness of the global markets, including the one at the perceptional level, let us remember the global saving glut that came into being in the aftermath of the Asian Crisis in the late 1990s.

In late 1997, a score of Asian countries, which were once praised as tiger economies, had collapsed when sudden capital reversals out of their borders broke their fixed exchange rate regimes.

Since then, large Asian central banks like China, where Renminbi’s exchange rate is kept under control, have come to hoard ever larger FX reserves in order to equip themselves with the leaning against the wind capacity if ever they feel the need to defend their currency. However, all these large FX reserves, where the USD was the dominant currency, were invested in the respective economies, and thus largely the US government bonds. That created a situation where China had pumped money into the US market like never seen before at the onset of the 21st century.

In plain English, China was exporting to the US, dollars were ending up in the FX reserves of the People’s Bank of China and then they were recycled back to the US through the US government bond purchases of China. That liquidity, which was pumped to the US, was then channeled into mortgage loans - even to those in the subprime (not-so-credible) market. Furthermore, as more and more money kept being poured into the US housing market, US house prices soared, and thus the values of the collaterals. Therefore, no one could really see the danger of pouring too much money into a subprime market until it was too late in May 2007. The rest is well-known history, the Fed had to step in and swap the liquidity with the toxic assets of the US banks, etc. We are not saying or hinting that the same will happen now; nor do we see the US banking assets as problematic or toxic now. This story should illustrate the interconnectedness between markets through the capital and liquidity flows as between China and the US.

There are, however, also connections between markets on the perceptional level. To articulate on that let’s continue remembering what happened then — the Eurozone meltdown. The problems that started in the US spread to the other side of the Atlantic when the European banks, after seeing the problems their US counterparts were forced to deal with due to their unhealthy subprime loans, checked the health of their exposures and it did not take them long to see their loans to some Eurozone countries were really problematic: namely, Greece, Portugal, Italy, Spain. So the credit crunch came and the Eurozone Debt Crisis hit. If one likes to draw parallels between the problems affecting the US banks and the European banks, similarities are there: both the US and the European banks have exposures to companies that are at risk of being negatively affected by the fragile economic recovery in the US and Europe and the rising interest rates. Rising interest rates also negatively affect the market value of the bond stocks in Europe as well just like in the US. Hence, SVB’s failure and the policy responses thereof are important. But that incident once again showed us all that the US and Europe once again fail to properly provide international investors with a good and healthy diversification option. Emerging markets are therefore a must alternative, despite their own peculiarities.