The East–West Divide in Europe

Looming storms resurface a multitude of fragilities in the Union of a Developed West and an Emerging East

As the European Union grapples with persistent inflation, deepening energy crisis, and geopolitical risks from the East, the ECB, rather ineptly, does not shy away from picking on bond markets since the latter merely do what they are supposed to do — distinguish between differing credit risks within the Eurozone.1 ECB’s preference to pick a fight with the markets rather than fight with the underlying issues of Europe is no good signal for the future health of the European economies.

Given the fact that the developed economies are hard–pressed under such a plethora of issues, it should come to no one as a surprise to see them on the verge of stagflation where the developed world is pretty much walking a tight rope between going into and out of a recession with a not–so–transitory–after–all inflation lingering. As a matter of fact, we observe that markets, worryingly, underprice the possibility of such a W–shaped recession scenario in the face of a protracted stagflationary period. (See: A Case for W–Recession)

Against such a backdrop in developed economies, the question in our focus lays with what awaits the European Union, as a whole with its Developed and Emerging economies, forming an East–West division within a Union that is already having a hard time dealing with a North–South friction. Surely, certain things like entrenched inflation, energy insecurity, and a war at the doorstep show a high degree of pass–through from the Developed Europe into the Emerging Eastern European economies. However, there are structural vulnerabilities that the Union is largely exposed to, and a resurface of these fragilities will likely exacerbate the already–ramping misery felt in both the Euro Area and the Emerging Europe in the coming months.

Vorsprung durch Rezession

Lately, the debate on whether the US has descended into recession has intensified over a range of data releases creating mixed feelings across markets and intensifying the divisions among economists. While the popular recession definition of two consecutive quarters of negative growth suggests a recession is already in the making, the Fed & Co, once again, are swift to defy a plausible contra case, of worsening sentiments2, by touting the labour market numbers3 in repudiating a recession — reminiscent foremost of the transitory debate on inflation as well as a reminder that we are yet to see the end of the post–truth tunnel, where objective facts are overwhelmed by feelings.

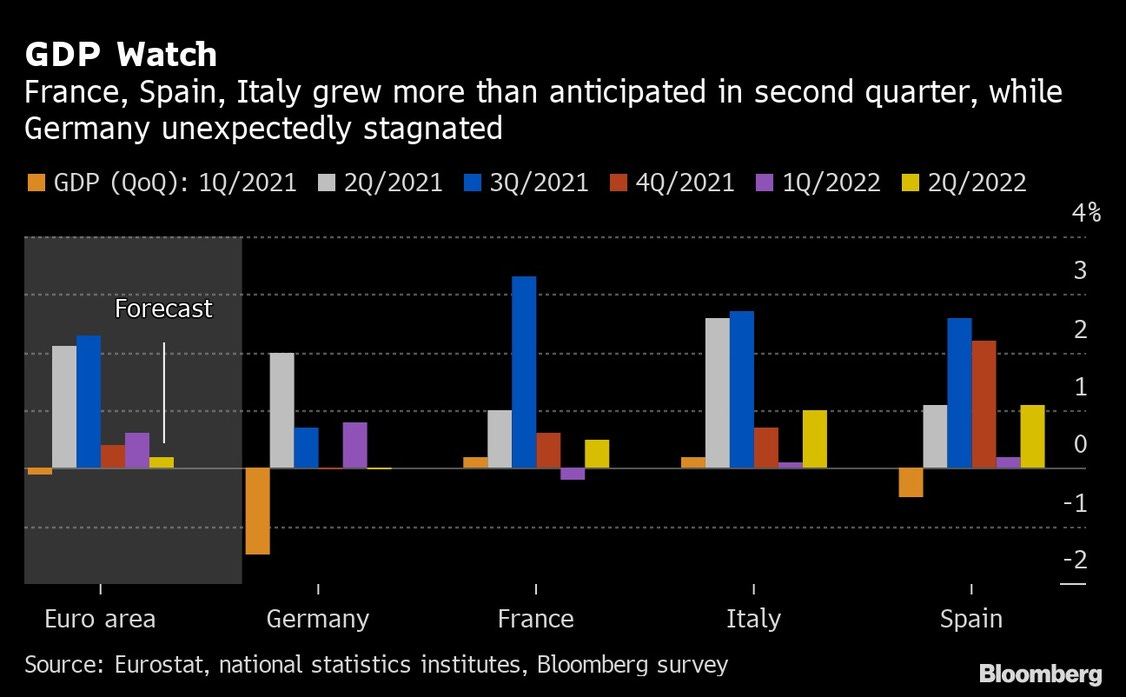

While the US goes through fifty shades of recession debate and ‘this–is–fineism’, a stronger recessionary momentum has been building up on the other side of the Atlantic. Experiencing a series of massive headwinds amplified by Russia, the industrial powerhouse of the EU, Germany, has not only posted its first trade deficit since 19914, but also has rather sharply slumped into stagnation5 with inflation rising multi–decade highs6 and consumer sentiment deteriorating rapidly7. In fact, given the dizzying pace of the developments, it should not take long before a stagnant German economy to weigh heavily down on the overall EU growth, as already reflected on the forecasts. (Figure 1)

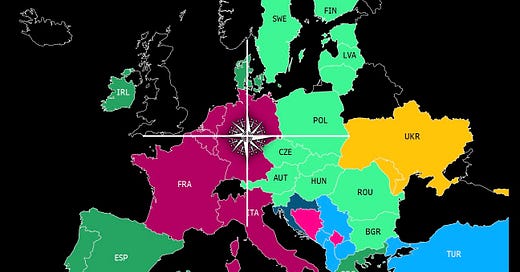

We believe the grim outlook forecasts paint for the Euro Area are applicable to the Union as a whole and are in line with our conception that there does not exist a singular European entity. Rather, there are five distinctive pieces (of North, South, East, West, and Gravitational Centre, with the latter being Germany) today that make up the Union. Given these parts are of vast difference, it is an enforced union, in need of some sort of glue, if you will, for it not to fall apart. We accordingly view Germany to have been in that glue role up until now. The question, however, is whether Germany will be able to continue this crucially binding role in the future? And if so, at what cost?

The North–South Axis

To set the tone for the rest of this article, let us once again recall a former article of ours: A Tale of Two Euros. In the article, we focused on the structural problems of Euro with primary focal point being the North–South divide within the Eurozone, having classified Eurozone countries into two groups as the North and the South with respect to their productivity differences rather than geographical locations.

Accordingly, we concluded that a currency union with such productivity disparities among its members, like that of Euro, cannot be an Optimal Currency Area. We further claimed that Euro was hence fundamentally flawed as a common currency project. In order to keep it alive as a currency, either its members need to form a fiscal union (and thus allow the fiscal transfers from the more productive to less productive members) or, in the absence of such a fiscal union (as it is the case now), productive members need to support the less productive members whenever they fail because of the current account imbalances that would accumulate over time within the Eurozone due to the very differences in productivity.

Indeed, that was the role Germany, though reluctantly, played during the Eurozone Debt Crisis in the aftermath of 2008 until 2011. Quite fittingly, Germany is well positioned for this role (of the rich member with deep pockets saving the whole continent from an looming collapse) in no small part thanks to its superior labour and capital productivity, albeit coupled with sluggish domestic real wage growth.

The East–West Axis

Nevertheless, we observe two matters that herald bad news. First, the North–South divide is not the only fracture we spot within Europe. Beyond the Eurozone, we note a similar division along the East–West axis. Hence the first bad news concerns the fact that there are more countries in the region whose economic destinies are inextricably tied to the performances of richer economies, especially to that of Germany.

Second, as already revealed in the opening remarks of this piece, European economies, as a whole, are in trouble and Germany, at the centre of both North–South and East–West axes (Figure 2), is certainly no exception. To put it succinctly, Germany today is in no position to rush to the rescue, let alone bail, of another country, if need be — as had been the case in the aftermath of the 2008-09 crisis.

A Game of Europe

Furthermore, we cannot help but mark a game of ‘gluing Europe together’ as aforesaid. Indeed, gluing Europe together is as costly as it sounds sticky — especially given it already is fragmented by its foundations.

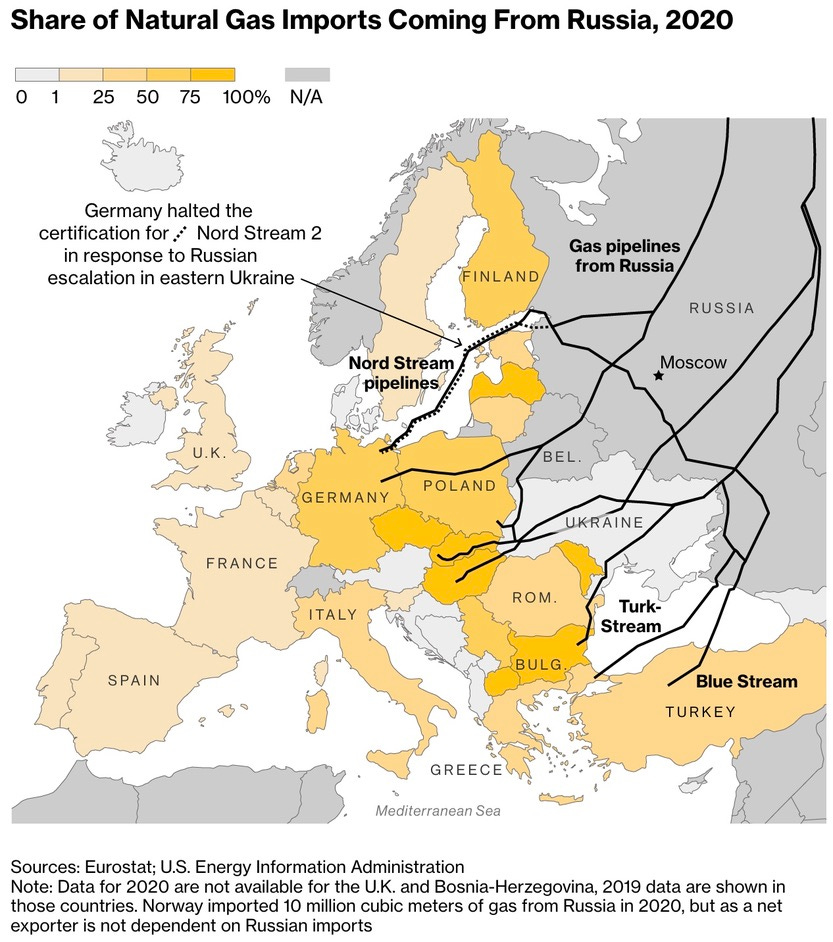

Naturally, there are gravitational factors pushing European countries together. And that is precisely why the attempt at a Union, in the first place. Nevertheless, there are forces pulling them apart, too. To illustrate, the Russian embargo that the Western Europe so fondly hoped for, only to be confronted by holdouts from the East on the grounds that such an embargo would hurt their economies more than they can cushion out. (Figure 3)

There are political and cultural factors pushing and pulling them, too. For instance, the recent election victory of the illiberal politics in Hungary has likely been a blow to the Western wishful fantasies about a liberal Eastern flank that would be more compatible with the Western one. As a matter of fact, it is the very same Hungary whose economy is at the moment facing a wreckage, encumbered by inflationary pressures that the Magyar Central Bank has so far been unable to contain despite a series of rate hikes. Consequently, this illiberal European ally is now on an anxious wait for the release of the funds from the same Union it has held out on the Russian sanctions for some economic breathing room.

Germany & Co.

Dig deeper and one unearths the trade flows that reveal why we hold Germany as the central gravitational force that help glue a Europe–wide Union together. The following tables underscore not only the importance of the West but especially of Germany on its own for all the other members in the North–South and East–West axes — ergo, the glue.

In Tables 1–4 below, we include 12 countries from Europe along with the US, Russia, and China. Of the 12 European countries, 6 form the Developed West according to the United Nation’s Geoscheme Classification using M49 Classification System. These are Germany, France, Austria, Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. The remaining 6 are classified as the Emerging Eastern Europe using the same classification system.

Attention should be drawn to how high the share of German imports for other countries compared to any other country. The only place German imports lag to the second place is in Belgium, where the Netherlands take the lead. That aside, German produces enjoy the top place in any other European economy’s imports.

The oft–touted fact of Germany’s dominance as the top export destination for the other European economies is also well documented in the following tables, with Germany being by far the largest export partner not only of the Developed Western, but also of the Emerging Eastern. Accordingly, we are of the conviction that Germany, beyond its supersets of North and West, form a gravitational centre and exudes influence across every corner of the Union.

On top of being the most important trade partner of each and every country in the Union, Germany is also the largest contributor to the EU budget every year, not to mention its high involvement in such key financial institutions as the EBRD and EIB. Thus, we observe not only that Germany has been the economic powerhouse of Europe, but also that it has been the German capital and German trade that has held the Union together.

All these notwithstanding, the German economy itself is going through protracted predicaments of both inflationary and recessionary risks that are more likely than not to exacerbate in the months to come. Hence, we caution that the very glue that has been holding the West and the East of the Union risks loosening. Repercussions would be grim and ripple all over the World.

Vulnerabilities

Having settled the prominence of Germany for the Union, we expect the aftermath of the fall of Germany from the game to take a dramatic turn. To begin with, the patching of Europe then will certainly be more problematic. Of course, Europe will be far from falling into pieces, and neither the EU nor the Eurozone are to take a coup de grace. At least, we cannot comprehend such developments unveil.

Yet, it is highly likely that certain structural vulnerabilities will resurface more strongly than ever. At the backdrop of all these, if one were to question what had gone wrong such that the state of the Union has come to face this brink, well, it is difficult to pinpoint an exact starting point.

1) Energy Policy

To articulate some of the standouts, still, we cover the energy dependency of the Union to Russia as a genuine, decade–long gamble that eventually cost dearly. It is truly difficult for us to grasp how the bulk of Europe, save France, with Germany leading the charge, has been undermined by popular activism on energy strategy and ended up dumping nuclear power, one of the cleanest sources of energy, in favour of the Russian energy.

With the schism between Russia and Europe that broke out with the Russia–Ukraine War, it is now excessively difficult for Europe to secure its energy supply and contain price pressures. It is the economic bankruptcy of the proverbial German economic machine that is concisely expressed by none other than the following tweet of the IIF’s Head Economist. (Figure 4)

On the one hand, it cripples Germany’s economic power and its power to transfer wealth within Europe, a capacity which could be much needed as the Eurozone, the Emerging Europe, and the World overall are entering darker days. On the other, the days of Germany enjoying its gravitational dominance within the Union owing to its position as the top trade partner of each and every country could no longer be taken for granted. For Germany could see its dominance challenged.

2) Politicisation of the ECB

The Union could further have put itself into a stronger position in its warmer days, as we exemplified above, if only its approach to energy strategy were wiser. However, that covers only one aspect and there is more to address than just energy. Take, for instance, a look at the ECB — the monetary authority of the Union. We observe an authority that is far from able to take effective decisions in a timely manner — enough to recall how sluggish the arrival at an interest rate hike decision has been8, despite the necessity of such a hike had become more visible months ago.

Moreover, let us remember the recent standoff between the very ECB and the bond markets on a nonsensical ECB intolerance of the interest rate differences between the Eurozone countries being unjustifiable. Reasoning behind concerns the political drive that the riskiness of all the Eurozone countries being the same — as detached from financial and economic literature as it could get, in our view.

Still, we are not convinced that both the sluggishness of the ECB and its EM–like picks on markets are due to a lack of technical expertise. In our view, it in no small part concerns the fact that the ECB is being increasingly politicized as an economic institution. As a result, its decision capabilities are hampered by cumbersome political negotiations to reach economic consensuses.

We hold that it is time to start verbalising the drag the cumbrous Union creates for the ECB’s ability to maintain its mandate. Nonetheless, we have yet to see any progress on account of the EU to address these issues, let alone grow more agile, especially at a time of increasing geopolitical risks that call for speedy moves from all parties, not to mention rampant market charges in any direction on narratives of any shred of optimism or pessimism.

3) Capital Oversupply

Next, the EU needs to work more on the issues with capital transfers to its Emerging Eastern members. In the economic literature, a well-known problem associated with such capital transfers is the oversupply problem. That is, international capital, often, is oversupplied to recipient economies because of two market failures: moral hazard and negative externalities problems.9 10 11

We are of the conviction that we have already witnessed this happen with the funds transferred from the Developed Europe in the West to the Emerging Europe in the East, given the funds transferred have in no way helped close the productivity gap between the West and the East in around two decade’s time. Else, we would have already seen a bettering trade balance between the West and the East.

4) Resource Curse

Approaching the relationship between the Western Europe and its either the Southern or the Eastern counterpart, we further note another well–known emerging economy disorder: curse of resources. Precisely, in the literature, it is called the curse of natural resources and refers to the nasty situation that if an emerging economy has valuable natural resources, there will be political fractions in the economy wrestling with one another to get access to the dividends from the natural resource all alone.

That being said, if one thinks of an entity like the EU, where capital transfers are almost impossible to halt, the politics in the recipient economies of these funds should shape around the discussions regarding the EU. When countries in the Emerging Europe (read recipients) clearly benefit economically from their ties with the EU, pro-Europe politicians should have the upper hand.

However, with economic hardships beginning to surface, then the opposite could happen. Extrapolating, we could witness in the future a harsher contra-European rhetoric being rooted in the politics not only of the peripheral Southern, but also of the Emerging Eastern. The end result would be further political instabilities within the Union.

Concluding

The nature and multiplicity of troubles brewing in Europe, and the gravity awaiting the Emerging Europe specifically, is only partially economic. There exist as many political headwinds as economic ones and it is extremely difficult to source which of the mounting risks, economic or political, trail to which vulnerabilities, irrespective of being categorised economic or political.

Nevertheless, the impending issues are of no size to be disregarded, by any measure. Further, current economic risks are gravitating toward thresholds beyond which it will be virtually impossible to take them for granted, per the attitude of late of monetary authorities. In stark contrast, however, tools employed so far by the Union as a whole, and the Emerging Europe in particular, against the fallout from the permeating nexus of inflation, energy, and geopolitical crises have mainly been limited to economic measures.

We remain of the opinion that, beyond inflation, the sheer materialisation of another economic risk, like a recession, could act as a perfect–storm catalyst in further resurfacing a multitude of fragilities — as much political as economic ones — undermining the feeble foundations of a Union we, alas, monitor to be dormant.

European Central Bank (2016): “Dealing with large and volatile capital flows and the role of the IMF”, Occasional Paper Series, No 180. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecbop180.en.pdf

Bank of International Settlements (2021): “Changing patterns of capital flows”, CGFS Papers, No 66. https://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs66.pdf

Korinek (2017): “Regulating capital flows to emerging markets: an externality view”, NBER Working Paper Series, 24152. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w24152/w24152.pdf

Has this post been forwarded to you? Feel free to subscribe below:

Please note that views expressed here do not constitute investment advice. Rumelia Letters by Opes Rumelia.